It was a particularly chilly cold case. At 1 am on November 18, 2010, officers from the Los Angeles Police Department responded to reports of gunfire in a leafy cul-de-sac near Universal Studios. They found Jong Kim lying in front of his home and shot at least five times. Kim, a 50-year-old liquor store owner, later died in a hospital without regaining consciousness.

The most promising clues were grainy surveillance images that showed a two-tone Honda Prelude with a sunroof and fancy rims, but no visible license plate. Paperwork revealed a veritable haystack of vehicles—5,000 Preludes registered in Los Angeles County alone.

Despite a $50,000 reward for information, the investigation stalled for more than a year. Then in May 2012, detectives turned to a new Automatic License Plate Reader system. ALPRs use digital cameras attached to buildings, street lights, and patrol cars to snap photos of passing cars. Computer-vision technology can determine the make and model of the car, and “read” the license plate—turning public streets into massive databases of almost every car on the road.

After looking at hundreds of photos, detectives focused on cars with the suspect Prelude’s modifications. One stood out. Although it was painted a different color in 2012, officers searched through the ALPR database and confirmed that in 2010 the car matched the surveillance video. It was enough to identify a suspect, who in 2015 was convicted of Kim’s murder and jailed for 50 years.

The analysis was made possible by software provided by Palantir, Peter Thiel’s shadowy intelligence startup. The LAPD was one of Palantir’s first local law enforcement customers, after it had cut its teeth on Pentagon, CIA, and NSA contracts. Since signing with Palantir in 2009, the LAPD has spent more than $20 million on its software and hardware.

Documents obtained through a public-records request suggest at least $5.8 million of that went to ALPR technologies.

Hundreds of Requests a Day

The LAPD has never divulged how many ALPR searches it conducts. But an email obtained by WIRED through the public record request says its police officers tapped the system 200 to 300 times a day in 2016. Los Angeles County sheriffs performed a similar number of searches through Palantir, according to the email. Police in Long Beach, the city south of LA, made an additional 30 searches a day. Together, the three departments make hundreds of thousands of searches a year.

It’s hard to put that number in perspective because there are few statistics on police use of license plate readers. However, Peter Bibring, director of police practices for the American Civil Liberties Union of California, considers the total “enormous.” He says it shows that it is now standard practice for officers to use ALPR “as a surveillance tool” even when “officers have no reason to believe a driver was involved in any criminal activity.”

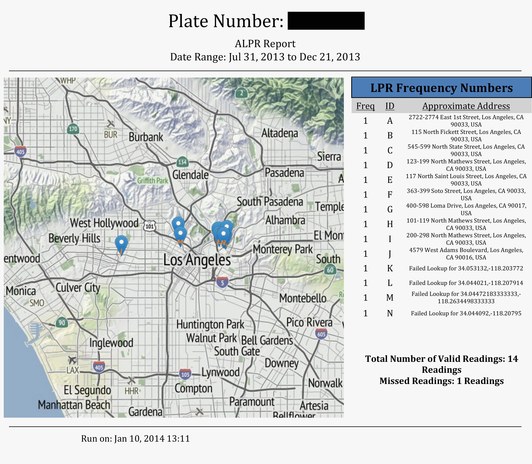

Using Palantir’s software, LAPD officers can see everywhere a car has been photographed in a given time period.

The LAPD has not said how many ALPR cameras it owns or has access to, although documents show that it shares images with cameras from the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department, Long Beach, Glendale, and Burbank police, as well as with Burbank, LAX, and Van Nuys airports. It has also used images from civilian ALPR cameras, typically deployed in shopping malls, universities, and transit centers for security.

ALPR systems are now widely used by law enforcement in the US and around the world. Surveys collected by the federal Bureau of Justice Statistics in 2013 found that 93 percent of police departments in cities with 1 million or more people used ALPR. Even half the departments serving towns as small as 25,000 people have ALPR. One ALPR company, Vigilant Solutions, claims that it carries out over a billion license plate scans each year.

Such systems traditionally have been used by law enforcement to help locate stolen vehicles. But when ALPR data is stored for years and then integrated with analytical systems like Palantir, it becomes much more powerful—and potentially open to abuse.

According to a Palantir user guide for the LAPD disclosed to WIRED, detectives start by logging in with their police credentials. When the system launched in 2009, officers had to type in why they were searching. Many would just enter “investigation” or the numeric code for a crime, like “459” for burglary, according to a 2014 email to users from John Gaw, a sheriff’s department sergeant responsible for working with Palantir.

Gaw warned Palantir users to better justify requests for ALPR searches, lest the department attract more attention from civil liberties groups. “[We] are facing potential limitations on the use … of the ALPR database by the ACLU,” he wrote. “We may be challenged to … show we are … making sure every user has a valid reason.”

Officers misusing law enforcement databases for their own purposes is a perennial problem at the LAPD and elsewhere. Some officers weren’t happy about Gaw’s team auditing ALPR requests and questioning vague rationales. “Unfortunately they have been contacting every user that puts in an unacceptable search reason,” wrote another LASD sergeant, Peter Jackson.

Searching by Plate Number, or by Area

In its latest version that went live in May 2016, called ALPR 2.0 or TBird, Palantir’s ALPR system requires users to enter a specific case number, and to select a purpose for each search via a pulldown menu. However, some of the reasons are vague, such as “protect critical infrastructure” or “protect the public during events.”

“The broad language for categorizing searches suggests that no indication of criminality is required to make a query,” says the ACLU’s Bibring. “If that’s the case, it’s basically the Wild West for when officers can query millions of data points.” Neither Palantir nor the LAPD responded to multiple requests for comment on this story.

Once in the system, detectives have several options. If they have a full or partial plate number, they can search using that. The system will then display matching plates, and a map view showing every time each plate was captured by the ALPR system.

A Timeline button brings up a chart showing how many times a plate has been searched, while a Freq Analysis feature displays a table showing those hits by time of day, and day of the week. These can help detectives spot patterns, such as where a vehicle’s driver might live or work.

Palantir’s TBird also works in reverse. Users can draw a circle on a map, then ask for a list of all the license plates spotted in that area at a given time. Sarah Brayne, a sociologist at the University of Texas at Austin who studied data surveillance at the LAPD for several years, detailed how this helped solve the murder of someone dumped at a remote tourist location. A nearby ALPR camera captured three cars around the time the body was dumped. The registered owner of one of the cars was affiliated with a gang then at war with the victim’s gang. Using that information, officers obtained a search warrant, examined the car for evidence, and arrested a suspect.

Not every police department with ALPR can use the technology as a time machine. Sixteen states and numerous cities have legislation regulating use of ALPR. Some limit how long data can be retained—from three years in the case of Colorado, to just 21 days in Maine. Los Angeles County keeps ALPR data for at least five years, whereas the California Highway Patrol can only hold it for 60 days. In the absence of regulations, several private companies specify that they will retain ALPR data “as long as it has commercial value.”

Palantir’s TBird can also be set to automatically track cars spotted in the greater Los Angeles area, sending users an alert whenever they are captured by an ALPR device.

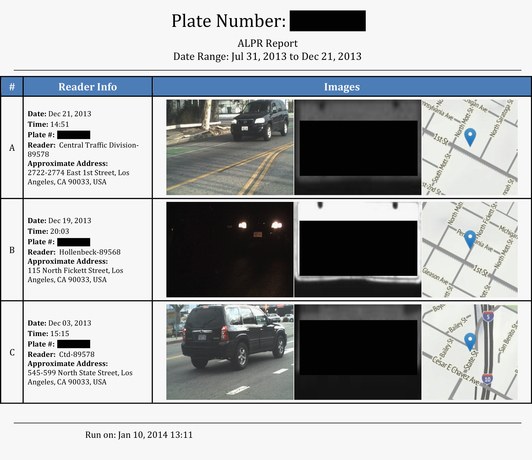

Officers also can see details of each sighting.

Palantir/LAPD

The powerful tool quickly became popular among LAPD detectives. “Due to a lot of hard work and promoting by training, Palantir has gained great traction,” wrote one of the company’s instructors at the LAPD in 2016. “Former detractors have come to now believe in the capabilities of Palantir.”

The same year, TBird got an upgrade, powered by artificial intelligence. Previously, the system could only identify license plate letters and numbers. Now it could also use machine learning to recognize the color, make, and style of vehicles photographed by ALPR cameras, as well as accessories like spare tires. Palantir used automobile image classification software from a Los Angeles-based startup called Intrinsics.

“The problem it’s trying to solve is the case where an eyewitness sees a vehicle leave the scene of a crime and all they get is a visual description, like it was a white Ford pickup,” says Intrinsics cofounder and CTO Eric Cheng. “[Our algorithm] allows investigators to sift through the database to find images that match that description.”

The ACLU’s Bibring says AI technology can be unreliable, and that agencies that use such systems should be “very clear to the public and to their oversight bodies what kind of surveillance they’re using, and what policies they have in place to protect against abuse.”

In its early days in Los Angeles, Palantir’s software was slow and glitchy, and some of its advanced features did not always work well, the records show. When the system failed, officers could complain to Palantir engineers embedded in the department. In 2013, a detective asked LAPD’s Palantir contact to try to identify a Chevrolet Impala used as a getaway car. “I ran the locations and times and came back mostly with patrol cars,” replied the Palantir engineer. “Clearly we need to step up our vehicle description … game to surpass [rival IBM software] CopLink.”

Emails from 2016 and earlier show LAPD officers generally liked Palantir’s ALPR system, but they complained about persistent slowness, maps not displaying properly, and connection problems. Palantir’s solution: LAPD should buy more technology “cores” (hardware and software packages), including two dedicated to the ALPR system—at a total cost of $280,000.

Records show that many ALPR systems, including some used by the LAPD, LASD, and Burbank police, as well as by LAX and Burbank airports, have relied on software from 3M called BOSS. Data from the 3M systems were then integrated into Palantir. The Electronic Frontier Foundation previously found that more than 100 cameras using 3M’s software were freely accessible online, including live video feeds.

Palantir’s software also has on occasion lost important data, the records show. In 2014, an officer complained that a car he had been tracking for several years had disappeared from the ALPR system. More worrying, perhaps, Palantir has misplaced hundreds of reported crimes. In 2015, an LAPD officer working on an annual crime analysis noted: “When I run all aggravated assaults for [my district] for 2012, Palantir only returns four for the year. In 2012, we had over 390 aggravated assaults.” That time, Palantir had simply misclassified the crimes; on another occasion in 2015, 327 violent crimes disappeared from another district’s records. It’s not known whether these problems were resolved.

Critics of ALPR say that the technology expands the net of Big Data surveillance. “Even though ALPRs are dragnet surveillance tools that collect information on everyone, rather than merely those under suspicion, the likelihood of being inputted into the system is not randomly distributed,” writes Brayne of the University of Texas. “Minority individuals and individuals in poor neighborhoods have a higher probability of being in the … surveillance net than do people in neighborhoods where the police are not conducting data-intensive forms of policing.”

LAPD remains committed to ALPR and to Palantir. In 2016, it signed a $2.9 million contract to upgrade TBird to ALPR 2.1, with unspecified new features. Palantir is reported to be considering a public offering next year, at a valuation above $35 billion.

Source: Wired.com. Written By Mark Harris.