Los Angeles fire officials are dramatically changing how rescuers respond to mass shootings after a gunman with a high-powered rifle mortally wounded a federal security officer in a shooting rampage last month at LAX.

Los Angeles fire officials are dramatically changing how rescuers respond to mass shootings after a gunman with a high-powered rifle mortally wounded a federal security officer in a shooting rampage last month at LAX.

The new goal is to have Los Angeles Fire Department paramedics and firefighters, protected by armed law enforcement teams, rapidly enter potentially dangerous areas during active shooting incidents to treat victims and get them en route to hospital trauma centers.

“The LAX incident really was a paradigm shift for us,” said Fire Department Medical Director Marc Eckstein, an emergency room physician and proponent of the more aggressive approach to rendering medical aid. “There are people whose lives may depend on us getting them out of there quickly.”

Tactical changes had been under consideration but were accelerated and disseminated through the ranks after the Nov. 1 shooting of Gerardo I. Hernandez, the first Transportation Security Administration officer killed in the line of duty.

That morning when rescuers arrived at Los Angeles International Airport, they set up a safe distance away and waited 15 minutes before they were told that Hernandez was lying by an escalator near the entrance of Terminal 3, according to interviews and dispatch logs obtained by The Times.

Police moved Hernandez to paramedics using a wheelchair, and he was taken to a Carson-area trauma hospital, where he was declared dead.

A coroner’s autopsy report found 12 bullets had ripped through the 39-year-old officer’s heart and other organs, and Los Angeles police Chief Charlie Beck has said no rescue effort could have saved him.

Hernandez’s death added new urgency to overhauling the Fire Department’s response to shooting rampages in which gunmen haven’t been apprehended.

With the changes, the department joins a growing number of fire agencies that are borrowing battlefield tactics of military medics to improve the odds of saving victims.

More than 250 people have died nationwide in mass shootings since 1999, federal officials note, including attacks last year on moviegoers at a Colorado theater and students at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Conn. The new imperative, experts say, is to reach those with life-threatening wounds quickly, stem their bleeding and get them to trauma centers as fast as possible.

“They need a surgeon,” said Battalion Chief Jeff Adams of the Orange County Fire Authority, which has rewritten procedures and retrained hundreds of rescuers in revised emergency response tactics being championed by the Obama administration.

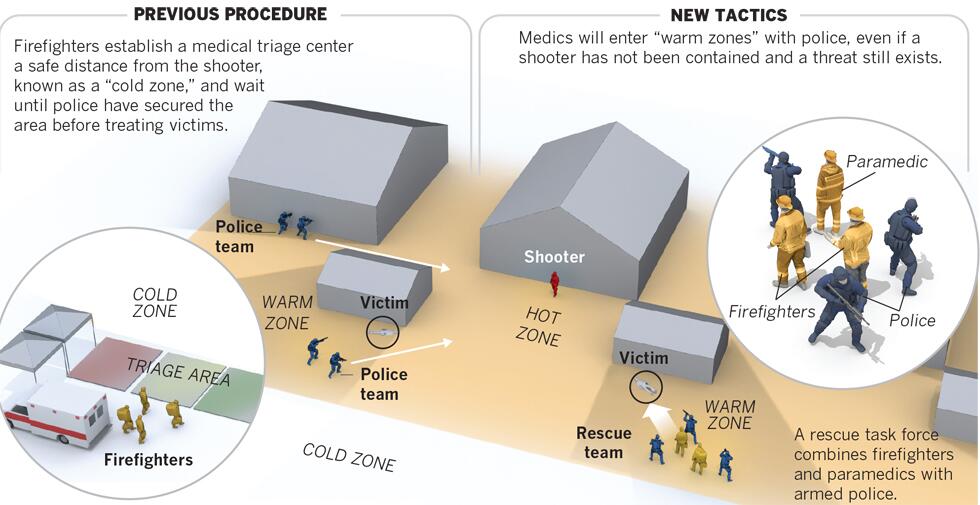

Recommendations issued by the Federal Emergency Management Agency in September call for fire department medics, working with police, to enter “warm zones” — areas near active shooters where a threat might exist — before the attackers have been fully contained.

Frontline rescuers in communities of every size need to be prepared, said U.S. Fire Administrator Ernest Mitchell Jr. “This can happen anywhere, any time. We don’t want to wait until after the fact and say what we would have done.”

Traditionally at shooting scenes, fire department rescuers have been held back in safe “cold” zones, awaiting orders to go to victims from law enforcement officers clearing “hot” areas where gunmen are active. Hot and warm zones are dynamic, experts say, and can change depending on the movements of the shooter.

The long-accepted tactics began to be scrutinized more closely in recent years with a rash of shooting incidents, starting with the 1999 Columbine school massacre in Colorado, when 13 people were slain by two gunmen who fired more than 100 rounds. Medical crews there were waiting nearby as a teacher bled to death.

An October 2011 attack on a Seal Beach hair salon by a gunman, who killed eight people, prompted Orange County to move to the forefront of large California jurisdictions embracing the new approach to mass shootings.

Nearly 1,000 Orange County Fire Authority personnel have been trained to don ballistic vests and enter warm zones under the protection of law enforcement officers, officials say. In addition, about 500 patrol deputies from the Orange County Sheriff’s Department have been trained to treat gunshot wounds and issued lightweight first-aid kits.

“It’s super-simple stuff. You’re slowing down or stopping the flow of blood,” said sheriff’s Sgt. Christian Hays, who has been conducting the deputy training. “The first-responder community is long overdue for this.”

In Los Angeles County, fire and police agencies say they need to revamp their responses but are trying to determine the best way to work together, said Dr. William Koenig, medical director for the countywide agency that oversees emergency medical care.

A training bulletin issued by interim L.A. Fire Department Chief James G. Featherstone provides new direction on dealing with law enforcement to set up warm zones and deploying “rescue task forces” to search for victims.

The department is ordering backpacks so rescuers can carry medical supplies, including tourniquets and thick combat gauze, to help stem heavy bleeding, Eckstein said. Firefighters, who already have Kevlar vests, are expected to begin drilling with LAPD officers soon, he said.

“You have to recognize that you’re possibly in the potential kill zone,” said Eckstein, who responded in June with a paramedic team to a deadly Santa Monica College shooting rampage and entered the scene with police. “It’s a whole new ball game for our people.”

Capt. Frank Lima, who heads the union representing more than 3,000 rank-and-file L.A. firefighters, said his organization supports rescuers taking on greater risk but stressed the importance of adequate police protection.

The L.A. Fire Department’s tactical changes are advancing amid investigations of the public safety response to last month’s LAX shooting, which also left two other TSA officers and a teacher wounded.

Fire Department dispatch records obtained by The Times, combined with coroner’s records and interviews, offer new details on the timeline of police and firefighter activity that morning.

At 9:28 a.m., the Fire Department’s 911 center was contacted by airport police, who reported a shooting in the Terminal 3 ticketing area with “multiple victims.”

Within two minutes, the first of more than 50 ambulances, fire engines and other units were dispatched to the airport, the records show.

At 9:35 a.m., the first rescuers arrived on the scene, and a paramedic ambulance reported: “LAPD said shooting is still active.”

Ten minutes later, dispatchers reported a person shot inside the terminal near a passenger gate. They noted that the “scene is clear per LAX PD.”

At 9:50 a.m. — 22 minutes after the Fire Department was summoned by police — rescuers at the scene were told that a TSA employee was at the “bottom of the escalator in the ticketing area of Terminal 3,” where authorities say Hernandez was shot.

Officials are continuing to investigate when the wounded officer was discovered by police and whether officers attempted to administer first aid.

At 9:52 a.m., Fire Department rescuers were told to move to the upper level at Terminal 2, east of the shooting scene and closer to the entrance to the LAX roadway loop. Additional fire units staged on the upper level near the Southwest Airlines terminal, farther away from Terminal 3.

Sometime after the rescue units were relocated — the dispatch logs do not indicate when — police lifted Hernandez into a wheelchair and brought him to paramedics waiting near Terminal 2, according to records and interviews.

At 10:15 a.m., Hernandez arrived at the Harbor-UCLA Medical Center emergency room, according to the coroner’s autopsy, which cited hospital records. He was in cardiac arrest and declared dead at 11 a.m.

E. Reed Smith, medical director of the Arlington County Fire Department in Virginia and an advisor on the federal government’s new guidelines, said the LAX shooting was an example of standard “stage and wait” tactics.

That model “is not outside the norm,” he said. “But could it be better and should it be changed? My answer is yes.”

Source: https://www.latimes.com/local/la-me-ems-response-20131223,0,7894044.story#ixzz2oQmQ693F